Deep Dive RCA: The $2.5 Million Panic How a Silent PostgreSQL feature almost Cost Everything

Because sometimes, the real outage isn’t the crash it’s what you didn’t monitor.

The Incident

It started as a normal day for a high-volume e-commerce platform until the PostgreSQL production database suddenly went Read-Only.

Writes were failing.

Orders weren’t processing.

Revenue loss was snowballing.

Within the first hour, the impact was already nearing $2.5 million.

For 30 terrifying minutes, they were chasing ghosts, convinced it was a standard Disk I/O bottleneck.

The pressure to throw money at the problem and just ‘Scale Up’ was immense, but it was the wrong move.

That’s when the issue escalated to me.

Before We Continue...

If you’ve ever dealt with a near-death database experience, you’ll want to subscribe. Get these deep-dive RCAs and performance tips delivered straight to your inbox.

Root Cause Analysis

The problem wasn’t disk capacity. It was configuration.

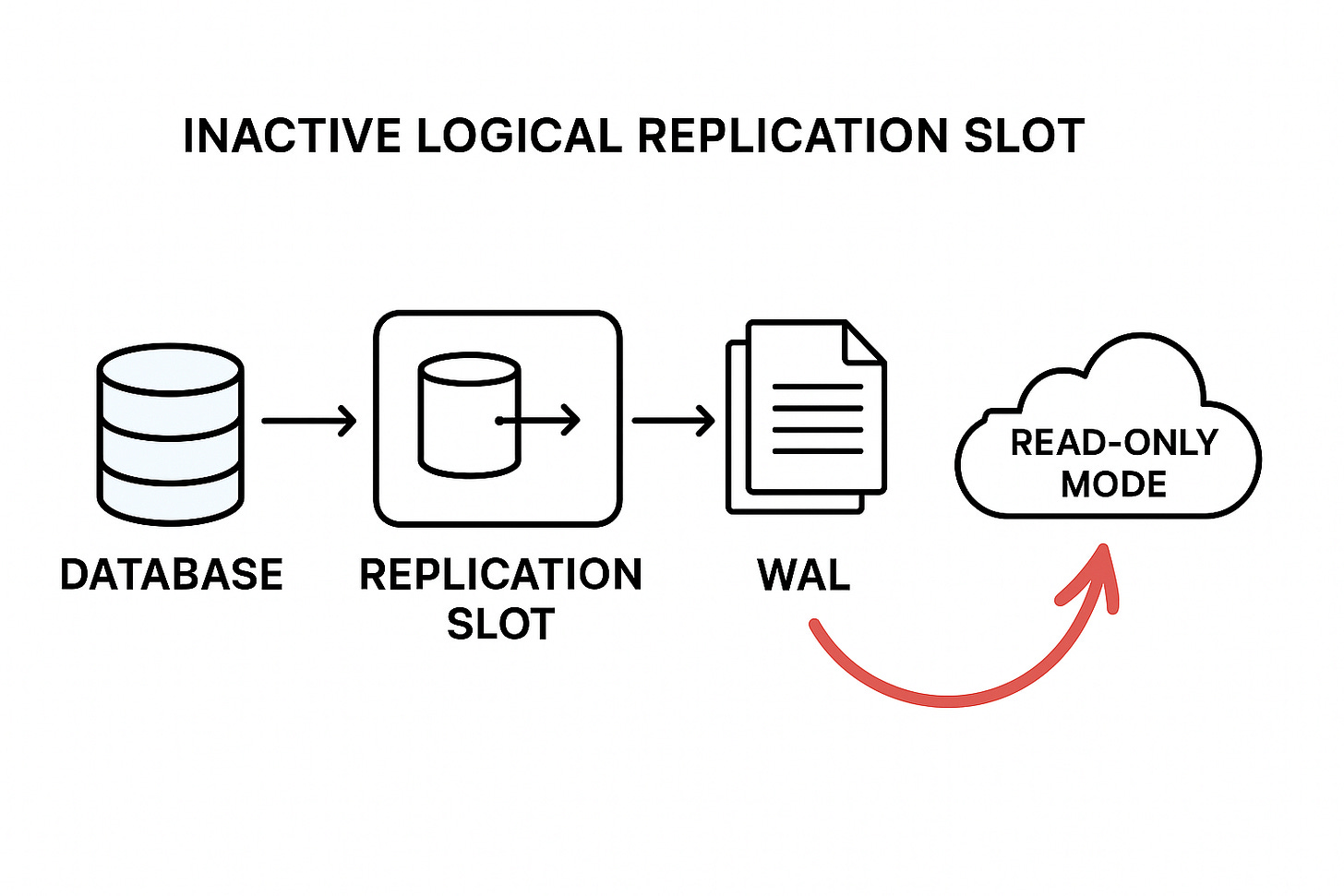

After digging through Azure PostgreSQL, one hidden culprit emerged inactive logical replication slots.

These replication slots were holding the database hostage, preventing PostgreSQL from cleaning up its Write-Ahead Logs (WAL) because it thought replicas still needed them.

In reality, the consumers were long gone but Azure PostgreSQL, loyal as always, was still keeping the old WAL segments “just in case.”

Over time, the accumulated WAL files completely filled the disk and when storage usage crossed 95%, Azure PostgreSQL automatically switched the server to read-only mode, a built-in safeguard to prevent data corruption.

When Azure PostgreSQL switches the server to read-only mode at around 95% disk usage, it’s not random it’s a protective mechanism against potential data corruption or database crash that can happen when the disk becomes completely full.

What is Replication in PostgreSQL?

Replication is the process of copying data from one database server (primary/master) to one or more other servers (standby/replica/slave) to ensure high availability, fault tolerance, and workload distribution.

1000+ incidents.

70% Sev1.

Fortune 100 pressure.

One mindset that works every time.

I documented it here →

🚀 Discover the new PostgreSQL Health Report one SQL file to diagnose Sev-1 incidents in minutes and fix them fast!

Types of PostgreSQL Replication

Physical Replication (Streaming Replication):

What it is: The most common type. It copies the raw WAL files from the primary to the standby. The standby is an identical binary copy of the primary.

Use Case: Creating a High-Availability (HA) cluster. If the primary fails, the standby can be promoted immediately. Also used for read-scaling (directing read-heavy queries to the standby).

Logical Replication:

What it is: Copies data changes based on their logical meaning (INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE) rather than raw WAL bytes. It uses a publish/subscribe model.

Use Case:

Major Version Upgrades with minimal downtime.

Selective Replication: Replicating only specific tables or databases.

Cross-Platform Integration: Replicating data to non-PostgreSQL systems (e.g., streaming data to an analysis platform).

Our RCA culprit ($2.5M Panic): Logical Replication Slots are essential for this type of replication.

The Core Mechanisms: WAL and MVCC

The RCA hinges on understanding two fundamental PostgreSQL concepts: WAL (Write-Ahead Logging) and MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control).

1. Write-Ahead Logging (WAL)

WAL is a transactional logging mechanism that guarantees Durability (the ‘D’ in ACID).

Reasoning: To achieve both performance and reliability, PostgreSQL uses WAL. When a transaction commits, the changes are written first to the WAL file (sequentially, which is fast) before the actual data pages in memory are written asynchronously to the main database files (which is slow and non-sequential).

Purpose:

Crash Recovery: If the system crashes, the database can “replay” the committed changes from the WAL to restore a consistent state, ensuring no committed data is lost.

Replication: WAL is the stream of changes sent to replicas (standbys) and logical consumers to keep them synchronized.

2. Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC)

MVCC is the concurrency control mechanism that guarantees Isolation (the ‘I’ in ACID).

Reasoning: Instead of using restrictive locks that block readers when a writer is active (or vice versa), PostgreSQL allows multiple transactions to access data concurrently by maintaining multiple versions of a row (called tuples).

How it works: When a row is updated or deleted, PostgreSQL doesn’t overwrite it immediately. It creates a new version of the row (with a new transaction ID) and marks the old version as logically deleted (with the old row’s set to the ID of the transaction that modified it). Each transaction sees a consistent snapshot of the database taken at the moment the transaction started.

The Critical Connection: How WAL and MVCC Work Together

To truly master PostgreSQL, you must understand how WAL (Write-Ahead Logging) and MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control) interlock. They are two sides of the same transactional coin:

MVCC: The “What” and “When” of Data Consistency

MVCC defines the logical change. When you run an

UPDATE, MVCC doesn’t overwrite the old row; it logically “deletes” the old tuple (setting its Xmax) and creates a new tuple version (setting its Xmin).This system is purely about concurrency and isolation, allowing readers to see the old version while writers are creating the new one. It handles the question: Which transaction sees what version of the data?

WAL: The “How” and “Where” of Durability

WAL defines the physical recording of that change. Every one of MVCC’s logical actions (the marking of the old row, the creation of the new row) is immediately recorded in the sequential WAL stream.

This system is about durability and recovery. It handles the question: How do we make sure these changes survive a crash and can be streamed to a replica?

The Interdependence:

The MVCC system generates the internal changes required to handle concurrent transactions, but it is the WAL system that faithfully logs every single detail of those changes. A massive buildup of WAL (as we saw with the inactive replication slots) means that the server is being forced to retain the entire history of MVCC-generated row versions, guaranteeing their existence for a reader that will never show up.

Why Logical Replication Slots Matter

Each logical replication slot keeps track of how far a subscriber has read the WAL stream.

If a subscriber disconnects or is deleted but the slot remains PostgreSQL will never remove those WAL files.

That’s where things go wrong.

The Checklist Mindset Playbook for Managing Sev-1 Cases

This includes:

A proven incident-handling mental model

How to think clearly under pressure

How to avoid panic debugging

Get 25+ practical SQL queries.

If you manage production systems, this playbook will change how you operate.

After resolving 1000+ Sev-1 incidents for Fortune 100 customers at Microsoft, I rely on one checklist mindset that never fails and you can get it from here.

I documented it here →

The Hidden Threat: Inactive Slots

Here’s how you can identify them:

SELECT

slot_name,

slot_type,

active,

restart_lsn,

pg_size_pretty(pg_wal_lsn_diff(pg_current_wal_lsn(), restart_lsn)) AS retained_wal

FROM pg_replication_slots;Key Interpretation:

active=f(false): This means the slot has no consumer currently connected.wal_retained: If this value is growing or is substantial (e.g., in the hundreds of GBs or TBs) for an inactive slot, it’s an unexploded bomb.

The Fix

We didn’t scale storage. We cleaned up the ghosts.

-- Drop inactive slots safely

SELECT pg_drop_replication_slot(’your_inactive_slot_name’);

The moment we dropped them, storage usage plummeted instantly.

PostgreSQL resumed normal WAL cleanup, and the database returned to full read/write mode within minutes.

How to Detect This Early

Set proactive checks:

-- Detect inactive slots older than 24 hours

SELECT slot_name, active, restart_lsn

FROM pg_replication_slots

WHERE active = false;

Alert if:

Any slot remains inactive > 24h

Retained WAL > 10GB

Storage usage > 90%

Integrate these queries into your monitoring dashboard (Grafana, Azure Monitor, or Prometheus).

Key Takeaways

Don’t let replication slots linger audit them regularly.

Scaling up isn’t a fix it’s a delay.

Always monitor:

SELECT * FROM pg_replication_slots;Add replication slot checks to your maintenance scripts or alerting dashboards.

Final Thought

In PostgreSQL, replication is power but unmanaged replication is risk.

One inactive slot nearly cost millions not because PostgreSQL failed, but because we didn’t listen to what it was trying to tell us.

Want the Deep Stuff? Become a Paid Member

Paid members get instant access to:

Premium content with Deep dive into full RCA analysis, get actionable scripts, and Ask Me Anything via Email for Mentorship.